For quite a few years now Herefordshire’s libraries have fallen victim to budget cuts, and that doesn’t look to be changing any time soon. If those spaces are to remain at the heart of the community, it might take creative solutions to safeguard their longterm future.

Writing for the Shire, chairwoman of the Independent Libraries Association Emma Marigliano explains how independent libraries, once at the forefront of public learning, have fought back from near-extinction in the ‘80s to thrive at a time when many public libraries are facing the same fate.

________________

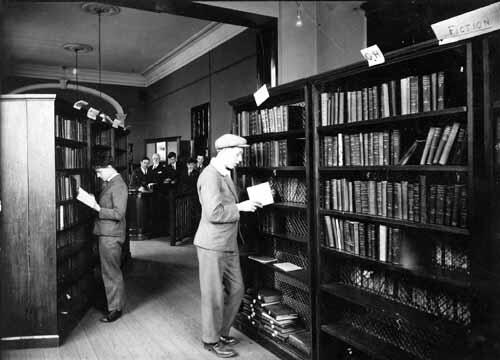

Before free public lending libraries were born subscription and proprietary libraries provided a public with the wherewithal to read and borrow books, newspapers, journals, magazines and periodicals – for a fee.

This meant, of course, that the service was not easily available to all. Mechanics Institutes were places of learning, and workers (mainly men) could get to read newspapers, but only these libraries – and there were many – afforded the opportunity for the circulation of books etc.

The shares (if it was a proprietary library, too) and the subscriptions maintained the building and allowed purchases and collection accessions. The proprietors and subscribers often represented the educated class of the town or city – the Polite Society, in fact; and the collections reflected their cultural tastes and reading habits – as well as a civic pride in how these collections were perceived.

The membership lists consisted of merchants, bankers, politicians, clerics and medical men (and sometimes women) and, through this newly discovered thirst for knowledge, information spread further and further afield quicker than ever.

Then came the free public lending libraries – starting from that city, already known for its radical and pioneering reputation, Manchester.

And once you no longer had to pay for the privilege of going into a library and borrowing books and reading the latest news from near and far, the subscription libraries began to feel a marked difference in their ability to survive.

Little by little subscription renewals were becoming increasingly difficult to attract and by the end of the beginning of the 20th century hundreds of these libraries were closing their doors for the last time. Two world wars didn’t help either and the vast majority of the libraries had disappeared by the mid-20th century. Some were just small village or town libraries, but there were many in the cities and larger towns that also couldn’t cope with free access to books and reading, so by the end of the 20th century fewer than four or five dozen were left.

In 1989 The Association of Independent Libraries (AIL) was formed by the Librarians of The Portico Library, The Leeds Library, The Birmingham and Midland Institute and The Athenaeum Liverpool to bring together the remaining independent libraries in Great Britain and Ireland with the purpose of supporting each other and sharing knowledge and experience that would enable them to not only survive, but thrive.

Starting off with around 18 members today the rebranded ILA (Independent Libraries Association) boasts 34 members and rising, counting amongst its ranks the smallest (Tavistock Subscription Library in Devon) and the largest (The London Library) with our latest member as far afield as the Channel Islands (The Priaulx Library in Guernsey).

How have we thrived? And how, particularly, at a time when public libraries are not only being redefined but also going down like flies ( for example an announcement last month revealed that Essex is planning to shut down a third - around 24 - of all its libraries).

Adaptation, rather than change, is the tactic of choice.

Charity status has meant that the membership could not long hold on to their exclusivity. The comfy armchairs in the reading rooms were not there to envelop the elderly gentlemen smoking their pipes over a good newspaper or having a good snooze; they became good seats for people who wanted to write, to study, to meet social and business acquaintances, to have a coffee, sometimes lunch – oh, and to read!

Spaces were made for lectures, presentations, performances, exhibitions, outreach and community projects, collaborations with the cultural, educational and heritage communities of the region; and doors were opened to all.

At the centre of the strategy lay the collections that remain the inspiration and focus for what the libraries stand for. Learning and knowledge. But for the many, not the few.

We’ve found that disillusionment with the direction of public libraries has sent more and more people – of all ages – to discover independent libraries from Land’s End to John O’Groats and beyond. When they enter our doors – most of them in historic buildings – the first reaction is “Wow! A library with books!”

Perhaps we’ve gone full circle and, once more, may be inspiring the public libraries to do what they set out to do. Be there for those who want to read and learn – and not just on computers.

________________

Emma Marigliano was Librarian of The Portico Library until the end of 2017 and saw it through its most crucial changes – that of opening its doors to the public and attaining charity status. She is currently the chairwoman of the Independent Libraries Association and has seen through the rebranding and new approaches to how the Association relates to its member libraries and their communities.

The ILA’s current President is Neil Pearson, best known as an actor (Drop the Dead Donkey, Bridget Jones (franchise), but also bibliophilic antiquarian bookseller who is also working to further the ambitions of the Association and its members.